Blood test may identify pregnant women at risk of premature birth

Posted: 8 June 2018 | European Pharmaceutical Review | No comments yet

New research has found biomarkers that accurately identified pregnant women who would go on to deliver babies up to two months prematurely…

New research has found biomarkers in maternal blood that accurately identified pregnant women who would go on to deliver babies up to two months prematurely.

This finding is important as doctors do not currently have ways to accurately assess which pregnancies will end with a premature birth, the researchers note. Additionally, using those same blood samples, the team found biomarkers in maternal blood that could estimate gestational age or a delivery date with comparable accuracy to ultrasound, but possibly at lower cost.

“This exciting cutting-edge research demonstrates why March of Dimes is investing in new ways to improve the health of moms and babies, especially to address the crisis of premature birth in this country and worldwide,” says Stacey D. Stewart, president of March of Dimes. “To date, no test on the market can reliably predict which pregnant moms will go on to preterm labour. March of Dimes is committed to finding new solutions and to giving all babies the best possible start in life.”

Premature birth affects 15 million babies each year worldwide and is on the rise in the United States. Recently released provisional data for 2017 from the National Center for Health Statistics show that the preterm birth rate in the U.S. has reached 9.93 percent, up from 9.86 in 2016, the third consecutive annual increase after steady declines over the previous seven years.

The studies were led by Dr Stephen Quake, an investigator at the March of Dimes Prematurity Research Center at Stanford University. Partners included scientists in Denmark and Alabama as well as at the March of Dimes Prematurity Research Center at the University of Pennsylvania.

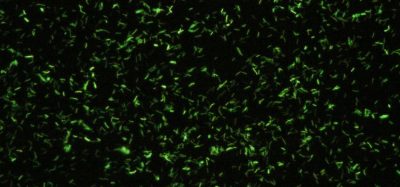

Dr David K. Stevenson, the principal investigator of the March of Dimes Prematurity Research Center at Stanford University, described the noninvasive blood test approach as a way of “eavesdropping on a conversation” between the mother, the fetus and the placenta, without disturbing the pregnancy. He added that today’s findings affirm the existence of a “transcriptomic clock of pregnancy” that could serve as a new way to assess the gestational age of a fetus. “By measuring cell-free RNA in the circulation of the mother, we can observe changing patterns of gene activity that happen normally during pregnancy, and identify disruptions in the patterns that may signal to doctors that unhealthy circumstances like preterm labour and birth are likely to occur,” Dr Stevenson said. “With further study, we might be able to identify specific genes and gene pathways that could reveal some of the underlying causes of preterm birth, and suggest potential targets for interventions to prevent it.”

In two separate cohorts of women, all at elevated risk of delivering preterm, the team identified a set of cell-free RNA (cfRNA) transcripts that accurately classified women who delivered preterm up to two months in advance of labour. In another cohort of healthy pregnant women, the team found that measurement of nine cfRNA transcripts in maternal blood predicted gestational age with comparable accuracy to ultrasound.

The researchers noted that both tests will require validation in larger, blinded clinical trials.

The findings were published in the journal Science.