Robotic implant aids the treatment of oesophageal atresia

Engineers have created a robot that can be used to help treat babies with a rare birth defect that affects an infant’s oesophagus…

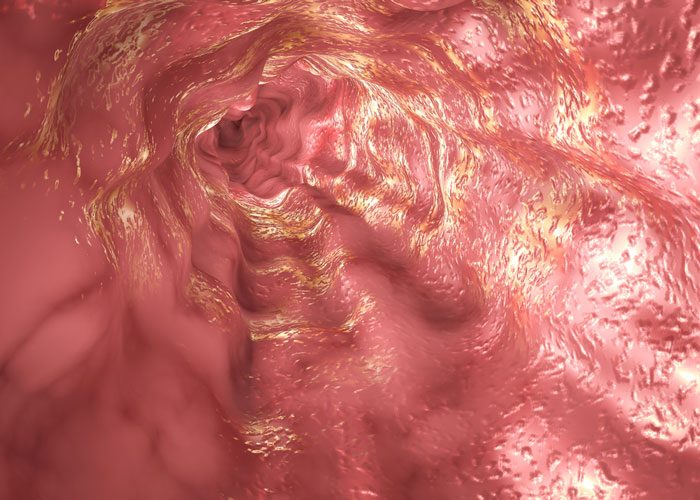

Researchers have created a robot that can be fixed into the body to aid the treatment of oesophageal atresia, a rare birth defect that affects a baby’s oesophagus.

Dr Dana Damian from the Department of Automatic Control and Systems Engineering at the University of Sheffield and her team from Boston Children’s Hospital have created the revolutionary prototype robotic implant which encourages tissue growth in babies.

The robot is a small device which is attached to the oesophagus by two rings. An incorporated motor then stimulates the cells by gently pulling the tissue. Using two types of sensors – one to measure the tension in the tissue and another to measure tissue displacement – the robot monitors and applies tissue traction depending on the tissue properties.

The robot’s function is inspired by the Foker technique of correcting the oesophageal atresia which involves manually pulling the tissue slowly using sutures over a period of time.

Dr Damian said: “Doctors have been performing the Foker procedure as they realised that tissue lengthening can be achieved by pulling on the tissue. However, it is unknown how much force should be applied to produce tissue lengthening. Although the technique is one of the best standards, sometimes the sutures surgeons attach to the oesophagus can tear which can result in repetitive surgeries or scar tissue can form that can cause problems for the patient in the future.

“The robot we developed addresses this issue because it measures the force being applied and can be adapted at any time throughout the treatment. With it being implanted in the patient, it means they have – in effect – a doctor by their side all the time, monitoring them and changing their treatment when needed.”

The study suggests that with this robot, babies would be free to move around and be allowed to interact with their parents while undergoing treatment, taking away some of the stress from both parties.

The implant is powered by a control unit which remains outside of the body, attached to a vest. This means that doctors can monitor the patient without impacting on the baby’s routine.

Dr Damian said: “The biggest challenge we faced was to design a robot that works in a technology-hostile environment and to develop a robust physiologically-relevant interaction with the tissue that promotes its growth when there are so many unknowns about the underlying mechanisms. The robot we designed had to be soft and durable, air and water impermeable, abrasion resistant, non-corrosive and be able to be implanted for long-term treatment.

“This is the first step in adaptive regenerative-based treatments of tissues. We have made a device that can provide long-term control of the tissue growth using onboard medical expertise. We further want to look at other tubular tissues, such as the intestine and the vascular system, to see if this sort of technology can be used to help with other conditions, such as Short Bowel Syndrome.”

Tissue growth has been an issue in the bioengineering field for many years, however, this research is a stepping stone to understanding how mechanical stimulation at the tissue level helps the cells multiply and how doctors can stimulate cells to grow using intuitive tools.

The research has shown cells will multiply in response to being pulled rather than stretching out of shape or scarring. Using the robot’s monitoring and control abilities, the treatment can be changed to suit the patient and to optimize the cells’ growth.

Professor Sheila MacNeil, Professor of Tissue Engineering in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at the University of Sheffield, said: “Increasing knowledge of how tissues respond to mechanical strain with the production of new tissue has been needed for a long while.

Doctors and researchers understand that tissues will normally grow in response to traction forces, for example, this occurs naturally during pregnancy as the growing baby increases the pressure inside the mother, the abdominal wall and skin increase in area to relieve the tension generated from stretching these tissues. Plastic-surgeons have copied this trick by placing an inflatable balloon under the skin and inflating it over a period of weeks to expand skin and they then use this “extra skin” for reconstructive surgery for the patient.

“The development of this robotic implant is a breakthrough in applying the knowledge that tissues respond to strain with the production of new tissue in a practical and clinically useful manner.”