Genetic fault reduces the effectiveness of leukaemia treatment

Posted: 27 September 2017 | Dr Zara Kassam (European Pharmaceutical Review) | No comments yet

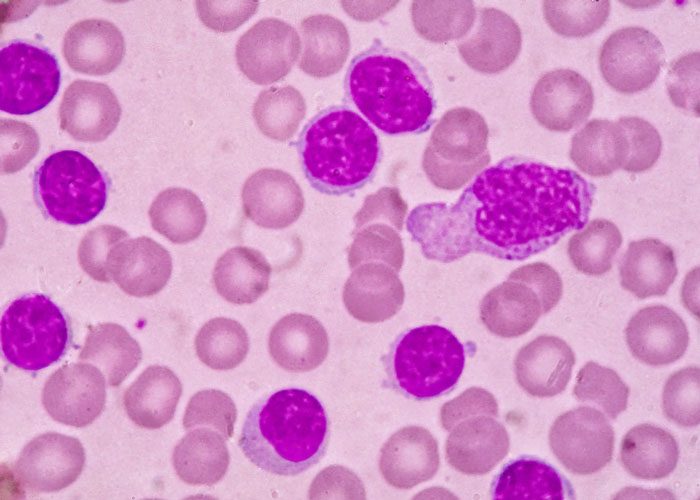

A genetic fault has been identified in people with an aggressive type of leukaemia that can significantly affect how they respond to treatment…

The findings come from a clinical trial led by the University of Birmingham that examined whether survival times for people with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) could be improved by adding a biological drug called vorinostat to the current standard treatment, a drug called azacitidine.

Although no additional benefit was seen with the new combination, people had a significantly worse outcome if their cancer cells carried a mutation in the CDKN2A gene. The results may help doctors tailor treatment to improve the outlook for patients.

The trial, called RAvVA, delivered at 19 hospitals across the UK through the charity’s ‘Trials Acceleration Programme’ (TAP). The results of the trial have now been published in the journal Clinical Cancer Research.

For those who are fit enough to tolerate it, the best chance of a long-term cure for AML involves intensive chemotherapy followed by a stem cell transplant.

However high-dose chemotherapy is poorly tolerated by older patients for whom the recently developed drug azacitidine, which can be delivered as an out-patient, represents an important new treatment option.

Although the exact way azacitidine works is unknown, it is believed to interfere with DNA in cancer cells and restore the activity of genes that control the rate of cell growth. Not everyone will respond, however, and all people eventually relapse. Its effectiveness varies greatly from person to person, and it is hard to identify who will benefit most before treatment begins.

Previous smaller clinical trials had suggested that outcomes for people with AML or MDS could be improved by combining vorinostat, which blocks cancer growth, with azacitidine.

The RAvVA trial treated 259 people with AML or MDS, with half the participants receiving a combination of azacitidine and vorinostat, and half receiving azacitidine alone.

It was found that adding vorinostat to azacitidine did not significantly improve treatment response or survival rates in people with AML or MDS. Those receiving the combination treatment survived for 11 months after diagnosis on average, compared to 9.6 months for people only treated with azacitidine.

While this result was disappointing, the study provides important new information that can be used to identify which patients are most likely to derive a clinical benefit from azacitidine therapy.

By correlating the depth of response of patients treated with azacitidine on the trial with the genetic makeup of their cancer cells at diagnosis, they identified that people who had faults in CDKN2A, IDH1 and TP53 genes had significantly reduced overall survival times.

Importantly, CDKN2A is a gene that regulates the cell cycle by making several proteins that control cell growth. As people who had mutations in this gene had a poorer outcome, the Birmingham team believe that one of the ways that azacitidine works is by causing cell cycle arrest. This information will guide the choice of new drug partners with the potential to increase azacitidine’s clinical activity.

This is the first time that mutations in the CDKN2A gene mutation have been linked to poorer survival in people with AML treated with azacitidine and strikingly patients with the mutation survived on average for 4.5 months, compared to an average of 11 months for people without it.

The team believe that testing people newly diagnosed with AML and MDS for CDKN2A, IDH1 and TP53 genetic mutations could help doctors tailor treatment for people who are less likely to do well.

The trial was led by Professor Charles Craddock, a Professor of Haemato-oncology at the University of Birmingham and Director of the Centre for Clinical Haematology run by University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust.

“This important trial, delivered through the Bloodwise Trials Acceleration Programme, has rapidly answered the important question of whether combining azacitidine with vorinostat improves outcomes for people with AML and MDS and emphasises the need for further studies with new drug partners for azacitidine,” said Prof Craddock.

“Importantly, the linked molecular studies have shed new light on which people will benefit most from azacitidine. Furthermore discovering that the CDKN2A gene mutation affects treatment response may be hugely valuable in helping doctors to design new treatment combinations in the future,” added Prof Craddock.

Dr Alasdair Rankin, Director of Research at Bloodwise, said: “This study demonstrates how important clinical trials are to help us understand not just whether a possible new treatment approach works or not, but why it succeeds or fails. By using samples from people with MDS and AML on this clinical trial, we have been able to understand the biology of blood cancer better. As a result, this trial has taught us much more about how doctors might treat individual people living with MDS and AML differently, so we can improve their care.”

Related topics

Anti-Cancer Therapeutics, Biologics, Drug Targets, Research & Development (R&D)

Related organisations

Trials Acceleration Programme', University Hospitals Birmingham, University of Birmingham

Related drugs

Related people

Related diseases & conditions

Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS)