Prostaglandin EI inhibits leukaemia stem cells

Posted: 26 September 2017 | Dr Zara Kassam (European Pharmaceutical Review) | No comments yet

Targeting leukaemia stem cells in combination with standard chemotherapy may improve treatment for chronic myeloid leukaemia…

Two drugs, already approved for safe use in people, may be able to improve therapy for chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML), a blood cancer that affects myeloid cells, according to results from a University of Iowa study.

One reason for this, explains Dr Hai-Hui Xue, Professor of Microbiology and Immunology at The University of Iowa (UI), is that there are two kinds of tumour cells — bulk leukemia cells that can be killed by tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) drugs, and a subset of cells called leukaemia stem cells, which are resistant to TKIs and to chemotherapy.

“A successful treatment is expected to kill the bulk leukaemia cells and at the same time get rid of the leukemic stem cells. Potentially, that could lead to a cure,” said Dr Xue.

With that goal in mind, Dr Xue and his team joined forces with Dr Chen Zhao, MD, UI Assistant Professor of Pathology, and used their understanding of CML genetics to look for small molecules or drug compounds that might be able to eradicate the leukaemia stem cells.

Focusing on two proteins known as transcription factors, the researchers showed that genetically removing the two transcription factors, Tcf1 and Lef1, in mice is sufficient to prevent leukaemia stem cells from persisting. Importantly, this genetic alteration did not affect normal hematopoietic stem cells.

Next, the researchers used an informatics method called connectivity maps to identify drugs or small molecules that can replicate the gene expression pattern that occurs when the two transcription factors are removed. This screening test identified a drug called prostaglandin E1 (PGE1).

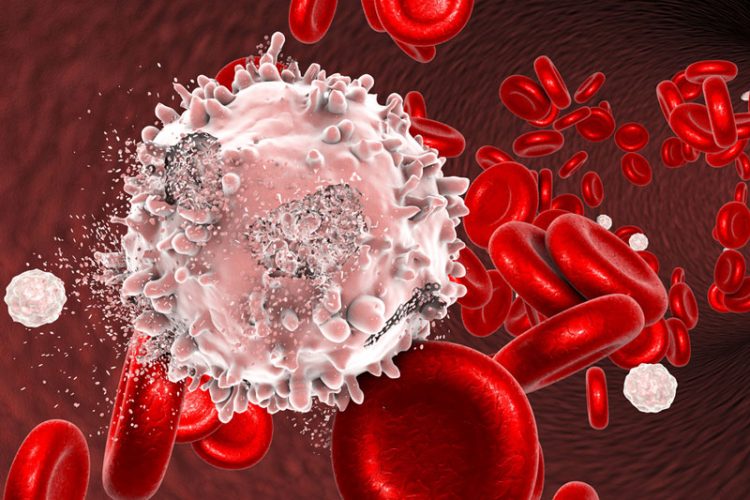

The team tested a combination of PGE1 and the TKI drug called imatinib in a mouse model of CML. The mice lived longer than control mice; 30 percent lived longer than 80 days compared to mice treated with only imatinib, all of which died within 60 days.

The team also looked at a different mouse model of CML, where human CML cells were transplanted into an immunocompromised mouse. When the mice received no treatment or were treated with imatinib alone, the human leukaemia stem cells propagated and grew to relatively large numbers. In contrast, when the animals were treated with a combination of imatinib and PGE1, those numbers were greatly reduced, and mice did not develop leukaemia.

“The results are a pleasant surprise,” said Dr Xue, “We do these kinds of genetic studies all the time — looking at transcription factors and what they do. This is a good opportunity to connect what we do at the bench to something that could be useful clinically.”

Investigating how the PGE1 works to suppress the leukaemia stem cells, the team found that the effect relies on a critical interaction between PGE1 and its receptor EP4. They then tested the effect of a second drug molecule called misoprostol, which also interacts with EP4, and showed that misoprostol also has the ability to combine with TKI and significantly reduce the number of leukaemia stem cells.

Both PGE1 and misoprostol are currently approved by the FDA for use in people. PGE1 is an injectable drug that is used to treat erectile dysfunction. Misoprostol is used to treat ulcers.

“We would like to be able to test these compounds in a clinical trial,” said Dr Xue.

“If we could show that the combination of TKI with PGE1, or misoprostol, can eliminate both the bulk tumour cells and the stem cells that keep a tumour going, that could potentially eliminate cancer to the point where a patient would no longer need to depend on TKI,” said Dr Xue.