Experimental gene therapy reverses sickle cell disease for three years

Posted: 14 December 2021 | Anna Begley (European Pharmaceutical Review) | No comments yet

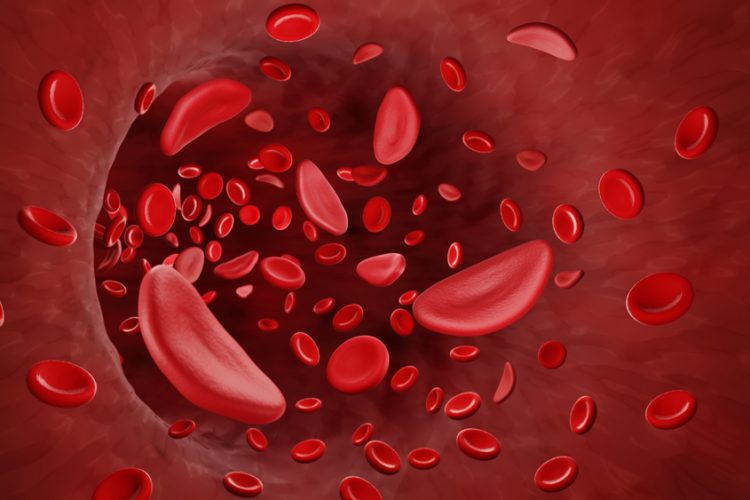

The gene therapy corrected the shape of some sickle cell patients’ red blood cells and eliminated episodes of severe pain.

A study of an investigational gene therapy for sickle cell disease at Columbia University Irving Medical Centre, US, has found that a single dose restored blood cells to their normal shape and eliminated the most serious complication of the disease for at least three years in some patients.

The single-dose therapy, tested on 35 adults and adolescents with sickle cell disease, essentially corrected the shape of the patient’s red blood cells, but also completely eliminated episodes of severe pain, caused when rigid, crescent-shaped red blood cells clump together and block blood vessels. The painful episodes often result in widespread organ damage.

Furthermore, the therapy completely eliminated severe pain crises in the months following infusion, ranging from four to 38 months—the longest period in which a gene therapy for sickle cell disease has been studied. The full results are published in New England Journal of Medicine.

With the new gene therapy, called LentiGlobin, blood-forming stem cells are collected from the patient’s blood. Harmless lentiviruses are then used to deliver a modified copy of the beta-globin gene into the stem cells. When the cells are later re-infused into the patient, they take up residence in the bone marrow and start making healthy new red blood cells.

“You cannot overstate the potential impact of this new therapy,” stated co-author Professor Markus Mapara. “People with sickle cell disease live in constant fear of the next pain crisis. This treatment could give people with this disease their life back. We hope this therapy will also be successful in younger patients so they can grow up without experiencing pain crises and live longer.”

However, one limitation of the gene therapy is that patients must first be treated with high-dose chemotherapy to eliminate old stem cells and make room for the modified stem cells, a process known as conditioning. Chemotherapy can be toxic and is associated with a small risk of cancer. Two patients in the trial developed leukaemia, which the researchers suspect was related to the chemotherapy, not to LentiGlobin treatment.

Researchers are currently working on less toxic approaches to conditioning the bone marrow before gene therapy. “The eventual goal will be to give this treatment as early as possible, well before patients develop organ damage and other complications of sickle cell disease,” added Mapara. “But before we can do this, we need to find a safer alternative to chemotherapy for conditioning strategies, such as antibodies.”

Related topics

Chemotherapy, Clinical Development, Gene therapy, Genomics, Research & Development (R&D), Therapeutics