Deception is not necessary for the placebo effect, finds new study

The study found that patients with irritable bowel syndrome taking open-label placebo reported similar improvements to those taking double-blind placebo.

A new study indicates that, contrary to popular belief, a patient does not need to believe that they could be receiving a pharmacologically active treatment to benefit from treatment with placebo.

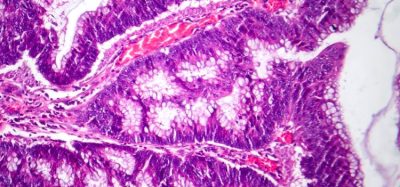

In the randomised clinical trial, researchers at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), US, found participants with moderate to severe irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) who were knowingly treated with a pharmacologically inactive pill (honest or open-label placebo) reported clinically meaningful improvements in their IBS symptoms.

Not only were their reported outcomes were significantly greater than those reported by participants assigned to a no-pill control group, perhaps more significantly, there was no difference in symptom improvement between those who received open-label or double-blind placebos. According to the investigators, these findings challenge the long-held notion that concealment or deception are key elements in the placebo effect.

“The clinical response to open-label placebo in this six-week trial was high, with 69 percent of participants who received open-label placebo reporting a clinically meaningful improvement in their symptoms,” said first and corresponding author Dr Anthony J Lembo, Professor of Medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology at BIDMC. “IBS is one of the most common reasons for healthcare consultations and absenteeism from work or school. Effective treatment options for IBS are limited and we hypothesised it may be possible to ethically harness the placebo effect for clinical benefit.”

The clinical trial enrolled 262 adult participants, aged 18 to 80 years old, with at least moderately severe irritable bowel syndrome, as measured by the validated IBS-Severity Scoring System (IBS-SSS). Participants were examined, filled out baseline questionnaires and were randomised into one of three study arms; open-label placebo; double-blind (which included double-blind placebo or double-blind peppermint oil); or no-pill control.

The open-label group received pill bottles labelled “open-label placebo” and were told that the pills inside were pharmacologically inert, but could make them feel better through the placebo effect. The double-blind group received pill bottles labelled “double-blind placebo” or “double-blind peppermint oil”. Participants in the double-blind group received either a placebo or an identical pill containing peppermint oil, but neither they nor the research team knew which they received. All participants who received pills were instructed to take one pill three times a day, 30 minutes before meals. The no-pill control group received no pills but otherwise followed identical study protocol. During return visits three and six weeks into the study, all participants completed questionnaires, were verbally asked about adverse events and briefly met with a study physician.

Lembo and colleagues found that improvement in IBS-SSS scores from baseline to the six-week endpoint was significantly greater in the open-label placebo group compared to the no-pill control group. Additionally, participants in the double-blind placebo group also saw superior symptom improvement compared to the no-pill control group, but the double-blind and open-label groups were not different from each other.

Next, the researchers performed a post hoc analysis of the participants who experienced large clinical improvements – those who improved by at least 50 points and by at least 150 points, considered strong and very strong clinical responses, respectively. A greater percentage of participants in the open-label placebo and double-blind placebo groups reported a 50-point reduction in IBS severity score compared to the no-pill control group (approximately 70 percent in each placebo group compared to 54 percent in the no pill control group). Similarly, approximately 30 percent of open-label placebo and double-blind placebo participants reported a 150-point reduction in IBS symptoms, compared to only 12 percent of the no-pill group.

“If the presumption that deception is necessary for placebos to be effective is false, then many theories about the mechanisms that drive placebo effects may need modification,” said senior author, Ted J Kaptchuk, Director of the Program in Placebo Studies and the Therapeutic Encounter at BIDMC, who with colleagues in 2010, published the results of the first randomised controlled trial to show that patients with IBS responded well to treatment with open-label placebo.

Subsequent research has demonstrated similar findings in patients with what they call subjective symptoms, including low back pain, knee pain, cancer-related fatigue, migraine headaches, menopausal hot flashes and allergic rhinitis. He continued: “Our finding that openly prescribed placebo may be as effective as double-blinded placebo has implications for clinical practice and for future research, especially in chronic visceral and somatic pain conditions.”

The research was published in Pain.