The case for immigration concessions: maintaining the UK’s competitiveness in science and technology

Posted: 27 March 2025 | Ana Sofia Walsh (Fragomen LLP), Rajiv Naik (Fragomen LLP) | No comments yet

Immigration law experts from Fragomen LLP discuss currently challenges in the UK’s visa system and propose recommendations for attracting science and technology talent that support the country’s competitiveness.

As scientific and pharmaceutical companies grapple to secure the world’s best talent, the science and immigration sectors are aware that the UK’s ability to attract global talent in science and technology is constantly under question.

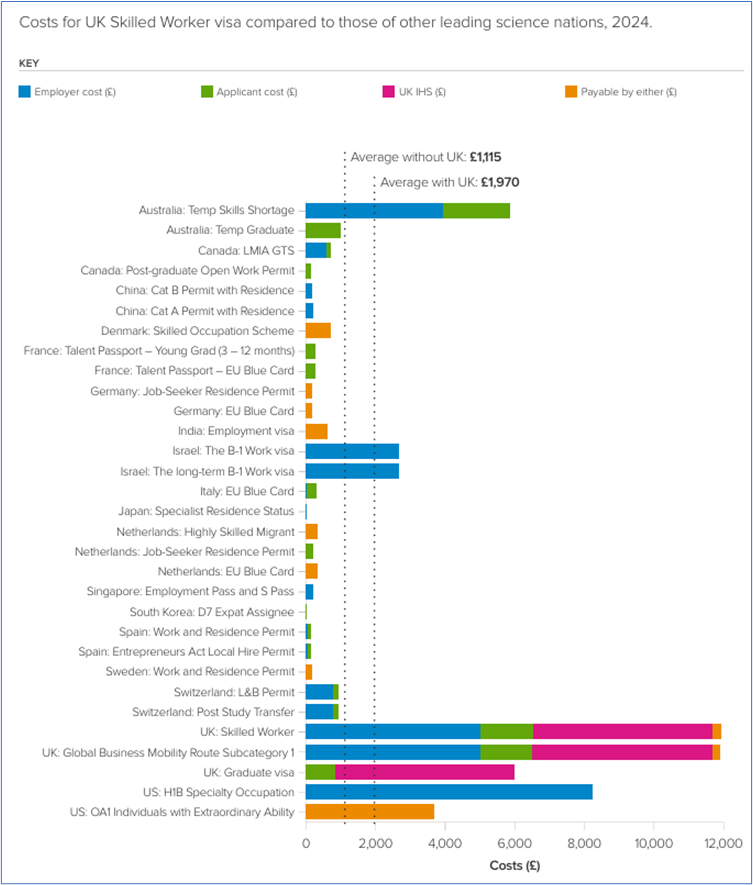

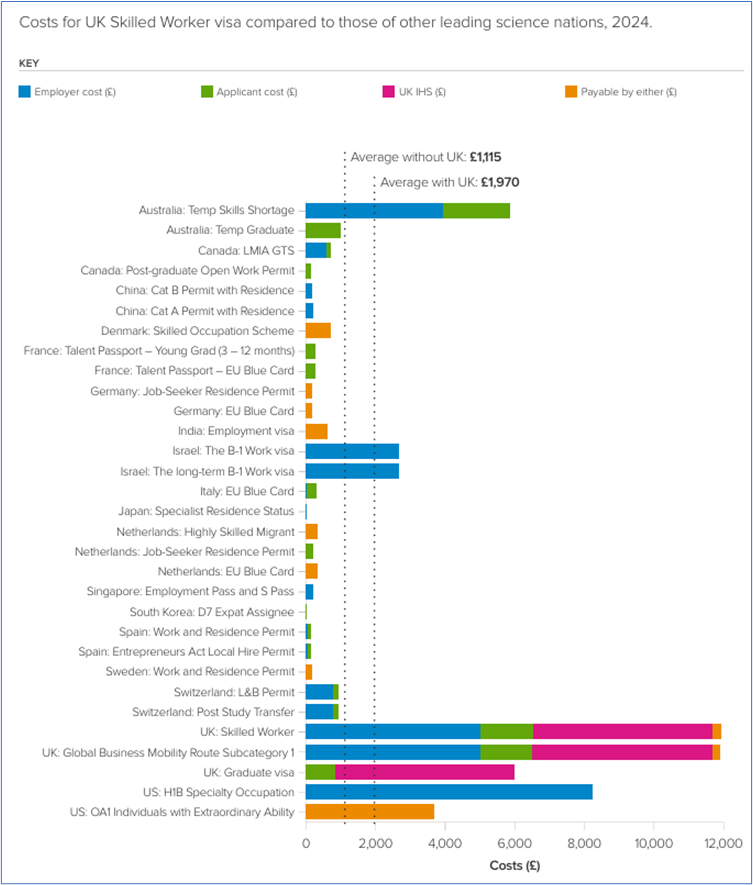

The House of Lords Science and Technology Committee recently warned that the country is in a ‘global competition for talent’ and that its visa system risks holding it back. Meanwhile, immigration costs continue to skyrocket, with the 2024 Royal Society report finding that the UK’s upfront visa costs are 17 times higher than those of other leading science nations.1

The government rhetoric largely focuses on how high/additional fees help fund public services, but there is little transparency about how this money is used. Could these costs be justified if they were directly reinvested into training UK talent? Without targeted concessions and a clearer breakdown of how the fees are used, the UK risks losing the best-in-class talent to countries that have adapted their immigration regimes to attract and retain top talent.

To help the UK to catch up, equalise, and future-proof itself in the global competition for science, pharmaceutical, and tech talent, we propose several considerations:

Catch up: reforming qualification requirements

Many leading nations now recognise that skills and experience, rather than formal academic qualifications, are often the best indicators of ability”

A significant governmental shift in thinking, particularly in Europe, is that academic achievement (notably degree qualifications) is the decisive factor when it comes to identifying top talent. Many leading nations now recognise that skills and experience, rather than formal academic qualifications, are often the best indicators of ability.

These include:

• The EU Blue Card, which offers a work and residence permit for highly skilled professionals, now allows professional experience to substitute for degrees. Only three years of relevant experience is required for tech roles in some EU countries.

• Sweden and Denmark allow employers to hire foreign talent without requiring them to submit degree certificates upfront. Instead, they trust employers to assess qualifications internally.

• France and Latvia allow employers to provide reference letters to justify an applicant’s expertise, shifting the burden of proof away from the worker and towards the hiring company.

• Denmark’s Pay Limit Scheme evaluates an applicant’s salary as a benchmark for verifying experience, further reducing the evidentiary burden on applicants.

The UK remains behind on this front. The Global Talent Visa and Skilled Worker Visa still emphasise degree qualifications in many fields, limiting access for highly skilled workers who may have gained expertise through experience rather than formal education. The country could follow the lead of the EU and Nordic countries by offering alternative pathways for workers to prove their skills.

Equalise: making UK immigration costs competitive

The UK’s visa fees have been labelled as ‘national self-harm’ by the House of Lords.2 In stark contrast, other science-focused nations have taken a more balanced approach:

• Canada and Germany charge minimal visa fees for skilled migrants and provide clear reinvestment into integration and training programmes

• Australia’s global talent visa prioritises speed and affordability, offering a pathway for top-tier professionals without excessive costs

• Singapore’s Tech.Pass is deliberately designed to be affordable, aiming to attract world-class scientists and entrepreneurs.

The UK, however, continues to increase costs without explaining how the revenue is used. If fees were transparently allocated to training UK workers in STEM fields, they might be more justifiable.

How do the UK’s immigration costs compare?

A 2024 Royal Society analysis compared upfront immigration costs across eighteen leading science nations. With the UK’s costs being exponentially higher than its global competitors, reform is needed to remain an attractive destination for UK science talent (Figure 1).1

Figure 1: Costs for UK skilled worker visa compared to those of other leading science nations.1

Futureproofing: introducing short-term mobility pathways

With the UK’s costs being exponentially higher than its global competitors, reform is needed to remain an attractive destination for UK science talent”

Scientific and pharmaceutical companies have voiced that they, like many other businesses, would like to see an improvement in the UK short-term mobility policy. Many other countries with thriving science hubs have developed flexible work authorisation routes to accommodate short-term research and project-based work:

• Denmark’s Fast-Track Scheme allows trusted employers to bring in skilled workers for up to three months, with minimal red tape

• France’s short-term work permit exemption permits foreign experts to conduct certain activities (such as research and consulting) without requiring a full work visa

• Israel’s Hi-Tech B1 Work Visa is tailored specifically to the tech sector, recognising the need for flexible, short-term hiring options

• Germany’s ICT Short-Term Permit enables intra-company transfers for up to three months, streamlining corporate mobility.

In contrast, the UK’s visitor visa rules limit paid work to only 30 days and only in specific circumstances. Given the project-based nature of scientific research and collaboration, the UK could introduce a dedicated short-term science and tech visa. This could be modelled on Denmark’s Fast-Track Pathway, for example, where only trusted employers are allowed to sponsor short-term hires, ensuring a balance between flexibility and compliance.

Looking ahead: a more competitive market for UK science talent

Given the project-based nature of scientific research and collaboration, the UK could introduce a dedicated short-term science and tech visa”

The UK must act quickly to remain a destination of choice for science and technology talent. To do so, policymakers should:

1. Align qualification requirements with global best practices, recognising professional experience in place of formal degrees, where appropriate

2. Reduce or justify high immigration costs, ensuring that fees are reinvested into training UK workers rather than simply going into general taxation

3. Introduce a short-term mobility pathway that allows researchers and tech professionals to work in the UK for limited periods.

If the UK hopes to attract the brightest minds and fuel scientific progress, it must create a system that is not only competitive but also transparent and fair. It must be a system that understands the needs of business and that can adapt and recalibrate as the needs of the world’s leading scientific and pharmaceutical companies continue to evolve as well.

About the authors

Rajiv Naik is a Partner at immigration firm Fragomen LLP.

Ana Sofia Walsh is a Knowledge Management Director at immigration firm Fragomen LLP.

References

1. Summary of visa costs analysis – 2024. [Internet] Royal Society. 2024. Available from: https://royalsociety.org/-/media/policy/publications/2024/summary-of-visa-costs-analysis-2024.pdf

2. Stem Visa Policy Jeopardises Economic Growth And Amounts To ‘Act Of National Self-Harm’ Says Lords Committee. [Internet] UK Parliament. 2025. Available from: https://www.parliament.uk/business/lords/media-centre/house-of-lords-media-notices/2025/february-2025/lords-committee-warning-on-visa-policy/

Related topics

Biopharmaceuticals, Drug Markets, Industry Insight, Recruitment, Therapeutics