EU pharmaceutical legislation revisions: what are the implications for biopharma?

Posted: 20 December 2023 | Anne Dhulesia (L.E.K Consulting), Sean Dyson (L.E.K. Consulting) | No comments yet

Anne Dhulesia and Sean Dyson, Partners at L.E.K. Consulting, discuss the proposed revisions to EU pharma legislation and potential implications for biopharma companies operating in Europe.

In Q1 2023, the European Commission (EC) announced proposed changes to EU pharmaceutical legislation.1 The changes form part of the 2020 Pharmaceutical Strategy for Europe will impact pharma and biopharma companies operating in Europe.

The proposed changes to EU pharmaceutical legislation broadly aim to:

- Support innovation and boost attractiveness of EU market

- Ensure timely and equitable access to medicines for patients across the EU

- Address other ongoing issues, including antimicrobial resistance and environmental impact of medicines.

These proposed changes can be categorised into seven main themes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Changes in the European Commission’s proposal for pharmaceutical legislation fall under seven key themes, based on L.E.K. analysis (Source: L.E.K)

Key changes to pharmaceutical legislation proposed by the EC

The main changes proposed by the the EC include:

- Reduced baseline regulatory protection for non-orphan, orphan, paediatric and repurposed medicines, but with potential extension based on factors such as level of unmet need, trial design, indication expansion, or pan-EU launch within two years

- Improved medicine availability safeguarding procedures, including monitoring and earlier reporting of shortages, and temporary emergency marketing authorisations (TEMAs)

- Transferable data exclusivity voucher for novel antimicrobials

- Streamlined EMA committees and processes, including reduced MA procedure length from 210 to 180 days, regulatory sandboxes, and ability of EMA to update labels based on data submissions independent of MA holder

- Strengthened enforcement of current environmental requirements.

Changes to regulatory data protection periods are of particular interest to biopharma”

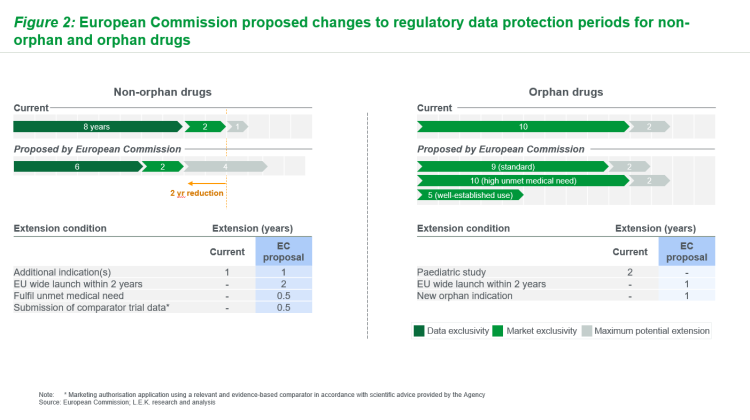

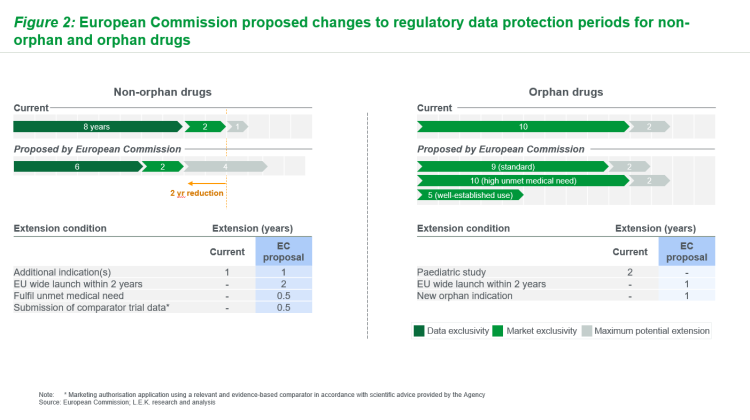

Changes to regulatory data protection (RDP) periods are of particular interest to biopharma (originators and generic / biosimilar manufacturers). Stakeholder reaction to original EC proposals suggests that changes are considered more favourable for generic/biosimilar manufacturers, given reduced RDP periods could lead to earlier generic/biosimilar entry for both non-orphan and orphan drugs (see Figure 2). Though extensions are possible, extension criteria could be challenging to achieve in practice (eg, pan-EU launch within two years, proof of unmet need).

Figure 2: European Commission proposed changes to regulatory data protection periods for non-orphan and orphan drugs (Source: L.E.K)

What are the latest amendments?

In October 2023, the European Parliament (EP) proposed revisions to the European Commission proposals with diverging views on various topics set out through two documents. 2,3

Proposed revisions include:

- Regulatory protection periods and incentives: Extended RDP periods for non-orphan drugs with broader definition of unmet need; reduced baseline exclusivity period for orphan drugs with stricter orphan designation criteria (discussed in more detail below)

- Safeguarding availability: Data and market protection suspensions upon compulsory licensing in health emergencies limited to indications and member states impacted by the emergency

- Antimicrobial resistance: Establishment of the ‘European Medicines Facility’ tasked with R&D of novel antimicrobials, instead of proposed transferable data exclusivity vouchers

- EMA committees and processes: Removal of the regulatory sandbox to avoid risks of potential rule circumvention, and MA holders must be consulted during the process of EMA updating product label (if data submission by another party)

- Environmental impact: Softened enforcement of environmental compliance (negative impact does not lead to automatic refusal of marketing authorisation).

Uncertainty around regulatory protection periods

The most significant variation compared to EC is around regulatory protection periods and incentives:

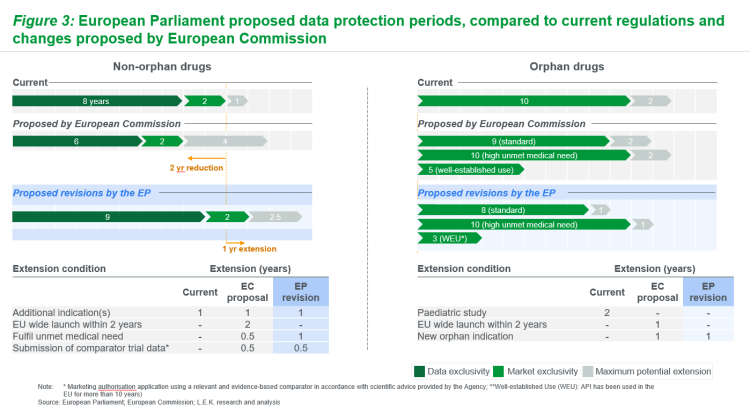

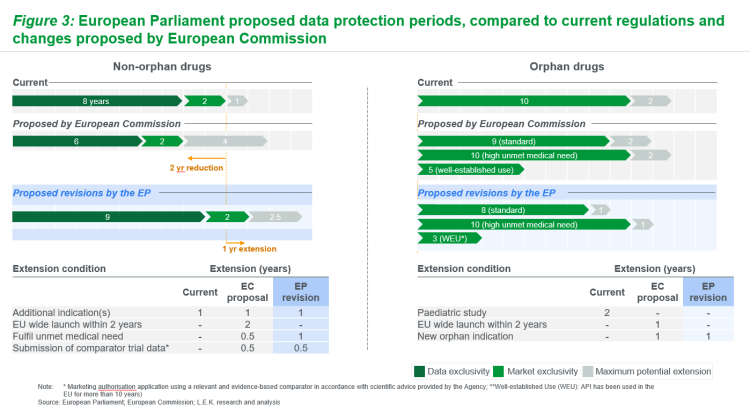

For non-orphan medicines, EP amendments extend baseline RDP by one year, in contrast to EC proposed reduction by two years (see Figure 3). EP additionally proposes two major changes to potential extension timelines compared to the EC. The first is removal of the RDP extension for pan-EU launch within two years, instead requiring manufacturers to submit to local P&MA processes upon request by the member state. The second is an adjustment of unmet need categorisation required for RDP extension; unmet need definition now encompasses ‘meaningful’ impact patient outcomes (notably including quality of life).

Like the EC proposal, the amended EP proposal seeks to ensure equitable access to medicines across the EU, through provisions to encourage pan-EU launch”

Like the EC proposal, the amended EP proposal seeks to ensure equitable access to medicines across the EU, through provisions to encourage pan-EU launch. However, EP attempts to alleviate biopharma concerns about the feasibility of pan-EU launch, and to further improve the attractiveness of the market to originators by extending the baseline RDP and loosening requirements for unmet need RDP extension.

For orphan medicines, EP proposals further reduce RDP periods compared to EC. EP proposes an incremental reduction of baseline RDP by one year and by a further two years for well-established use, compared to EC proposals. The period remains unchanged for those medicines fulfilling a high unmet medical need (‘substantial’ reduction in disease morbidity or mortality, but it is unclear on how exactly unmet need will be defined, and thus which drugs would qualify for this extended exclusivity. Additional changes in the EP include removal of pan-EU launch extension comparison (per non-orphan medicines) which serves to reduce potential extension from two years to one year.

Preparing for stricter standards on substances of human origin

A further impactful EP amendment is to orphan designation criteria, which appear to have become stricter compared to EC proposals. Orphan drug designation is current based on three criteria: fulfilling unmet medical needs, no satisfactory alternative or medicine of significant benefits, and rare condition or insufficient return on investment. While the EC proposes to abolish the ‘return on investment’ criterion, the EP proposes to retain this as a mandatory part of EMA assessment. As currently phrased, Parliament’s proposals suggest that orphan drugs deemed ‘sufficiently profitable’ could lose their orphan status after several years on the market.

Figure 3: European Parliament proposed data protection periods, compared to current regulations and changes proposed by European Commission (Source: L.E.K)

Implications for biopharma players

Given the conflict between EP and EC proposals, and ongoing discussions, legislation outlined here is unlikely to be final”

Given the conflict between EP and EC proposals, and ongoing discussions, legislation outlined here is unlikely to be final. However, it is clear that changes are likely to have meaningful impacts for biopharma players if adopted. It is important for biopharma players to consider how potential changes might impact internal strategy and portfolio decision-making.

If EP revisions are adopted, originators may see increased commercial value of non-orphan drugs dependent on RDP, given the one-year delay of generic / biosimilar entry compared to current regulations. By contrast, orphan drugs could become less profitable, more risky investments. The potential for a mandatory ‘return on investment’ assessment could lead to loss of orphan designation if the therapy is deemed ‘sufficiently profitable’. This could in turn lead to loss of benefits associated with orphan designation status (e.g., orphan marketing exclusivity or assumed ‘added benefit’ rating in Germany). Further, there is some uncertainty around on how ‘substantial’ reduction in disease morbidity / mortality, needed to access 1-year extension of data protection period, will be defined.

From the perspective of biosimilars manufacturers, potential launch dates for their products would likely change”

From the perspective of generics / biosimilar manufacturers, potential launch dates for their products would likely change, with longer time to entry for some non-orphan drugs but earlier potential launch of orphan generics. Given this, and increased optionality around RDP extension, launch readiness will be ever more vital.

Next steps for EU pharmaceutical legislation

The European Parliament’s amendments are in conflict with original European Commission proposals in several areas, notably regulatory data protection periods.

Key areas of uncertainty in the legislation will be clarified in due course”

It seems likely that there will be additional revisions and amendments are likely as the proposals pass through ENVI Committee. Key areas of uncertainty in the legislation will be clarified in due course (eg, thresholds for ‘high unmet need’ and ‘sufficient profitability’ of orphan therapies).

Biopharma will need to ensure they are up to date with changes to EU pharmaceutical legislation and are adapting their approach accordingly over the coming years.

About the authors

Sean Dyson is a Partner in L.E.K.’s European Life Science practice. He advises a diverse set of European pharmaceutical, biotech and financial clients in strategic planning, business development and commercialisation support. Sean holds a PhD in Clinical Neuroscience and an MA in Natural Sciences, both from the University of Cambridge, UK.

Anne Dhulesia is a Partner in the European Life Sciences practice. She has worked for various pharmaceutical / biotech companies and investment firms as part of her engagements at L.E.K., with a focus on growth strategy and commercial excellence across therapeutic areas of drug modalities. Anne has an MBA from London Business School, a PhD in Chemistry from the University of Cambridge (UK) and studied at the Ecole Normale Superieure (Paris).

References

- Reform of the EU pharmaceutical legislation. [Internet] 2023. [cited 2023Dec] Available from: https://health.ec.europa.eu/medicinal-products/pharmaceutical-strategy-europe/reform-eu-pharmaceutical-legislation_en

- European Parliament. Draft Report on the proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Union code relating to medicinal products for human use, and repealing Directive 2001/83/EC and Directive 2009/35/EC. [Internet] 2023. [cited 2023Dec] Available from: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/ENVI-PR-753470_EN.pdf

- European Parliament. Draft Report on the proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council laying down Union procedures for the authorisation and supervision of medicinal products for human use and establishing rules governing the

European Medicines Agency, amending Regulation (EC) No 1394/2007 and Regulation (EU) No 536/2014 and repealing Regulation (EC) No 726/2004, Regulation (EC) No 141/2000 and Regulation (EC) No 1901/2006 [Internet] 2023. [cited 2023Dec] Available from: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/ENVI-PR-753550_EN.pdf

Related topics

Biologics, Biopharmaceuticals, Biosimilars, Drug Development, Drug Markets, Orphan Drugs, Regulation & Legislation, Research & Development (R&D), Sustainability