Preventing contamination during biopharmaceutical production

Posted: 4 June 2020 | Victoria Rees (European Pharmaceutical Review) | No comments yet

A study that analysed QA/QC incidents at several biomanufacturing plants has revealed how companies can best hope to detect and mitigate virus contamination.

An entire sector within the pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical industries is dedicated to ensuring the high quality of drugs. If there are impurities or mistakes made during the medicine-making process, then patients who administer the drugs can face potentially fatalistic consequences.

To prevent this from occurring, quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC) processes need to be strict. However, there remain incidents when these can fail and contamination in manufacturing plants can happen.

Analysis of protein drug contamination

An MIT-led consortium conducted a study which analysed several incidents at manufacturing plants where protein drugs became contaminated with viruses. According to the researchers, these were all discovered before the drugs reached patients, but many led to costly clean-ups and in one instance, a drug shortage.

While the study focused on biopharmaceuticals, the researchers say the findings could also help biotech companies to create safety guidelines for the manufacture of new gene therapies and cell-based therapies, many of which are now in development and could face similar contamination risks.

…viral safety is best assured through complementary approaches”

The study, published in Nature Biotechnology, offers insight into the most common sources of viral contamination and makes several recommendations to help companies avoid such incidents in the future.

Speaking to European Pharmaceutical Review, lead author of the study Paul Barone, co-director of MIT’s Center for Biomedical Innovation’s (CBI) Biomanufacturing Program and director of the Consortium on Adventitious Agent Contamination in Biomanufacturing (CAACB), said: “From a product safety perspective, detecting a virus contamination is one piece of a broader approach to ensuring a protein therapeutic is safe. It is important to remember that all parts of this technique work together to ensure final product safety.”

Common causes of contamination

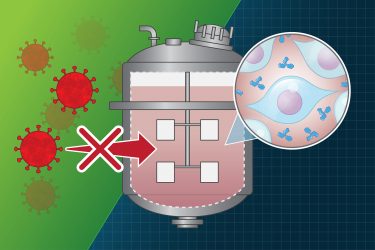

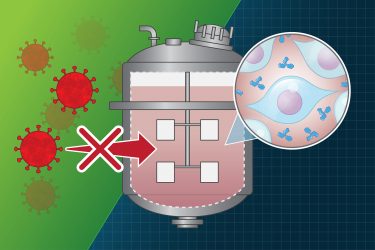

A new study from an MIT-led consortium, which analysed 18 incidents of viral contamination at biopharmaceutical manufacturing plants, offers insight into the most common sources of viral contamination and makes several recommendations to help companies avoid such incidents in the future [credit: Betsy Skrip, MIT Center for Biomedical Innovation].

Therapeutic proteins can be produced using recombinant DNA technology, which allows bacterial, yeast or mammalian cells to be engineered to produce a desired protein. Although this practice has a strong safety record, there is a risk that the cultured mammalian cells can be infected with viruses.

The CAACB, which performed the study, was launched in 2010 after a contamination incident at a Genzyme manufacturing plant in Boston. The plant shut down for about 10 months when some of its production processes became infected with a virus in 2009.

When incidents like this occur, drug companies are not required to make them public unless the incident affects their ability to provide the drug. A team from CBI assembled a group of 20 companies that were willing to share information on such incidents, on the condition that the data would be released anonymously.

The study focused on protein drugs produced by mammalian cells and analysed 18 viral contamination incidents since 1985. These occurred at nine of the 20 biopharmaceutical companies that reported data. In 12 of the incidents, the infected cells were Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, commonly used to produce protein drugs. The other incidents involved human or non-human primate cells.

The viruses that were found in the human and non-human primate cells included herpesvirus; human adenovirus; and reovirus. The researchers suggest that these viruses may have spread from workers at the plants.

“We found that for products manufactured in CHO cells, all of the contaminants were traced back to a raw material as the source. Therefore, implementing additional measures to remove or inactivate virus in higher risk raw materials would be expected to reduce that risk; several companies have taken this approach,” said Barone. “In comparison, all of the viruses that were found to contaminate human or primate cell lines were traced back to operators or the cell line itself. So, in designing any viral safety strategy, it is important to understand the potential susceptibility of the production cell line to different viruses and where those viruses might come from.”

Detection of the contamination

According to the authors, in many cases of contamination, incidents were first detected because cells were dying or did not look healthy. In two cases, the cells looked normal, but the viral contamination was detected by required safety testing. The researchers highlight that the most commonly used test takes at least two weeks to yield results, so the contaminating virus can spread further through the manufacturing process before it is detected.

Some companies use a faster test based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology, but this has to be customised to look for specific DNA sequences, so works best when the manufacturers know of specific viruses that are most likely to be found in their manufacturing processes.

Mitigating risk

Many of the CAACB member companies are exploring new technologies to inactivate or remove viruses from cell culture media before use and from products during purification. Additionally, the researchers say that companies are developing quick virus detection systems that are both sensitive and able to detect a broad spectrum of viruses. The CBI researchers are also developing on several technologies that could enable more rapid tests for viral contamination.

…the findings could also help biotech companies to create safety guidelines for the manufacture of new gene therapies and cell-based therapies”

“Identifying areas and materials that are of high-risk and mitigating those risks to prevent accidentally introducing a viral contamination is imperative. Our data indicates that operators are the suspected source of virus contamination when human or primate cells are used. Therefore, cell and gene therapies that use human cells should prioritise mitigating the risk of virus contamination from operators such as raw material handling, appropriate gowning, aseptic handling, sick policy, open processes, etc,” explained Barone.

A strategy that the report recommends and that some companies are already using is to reduce or eliminate the use of cell growth medium components that are derived from animal products such as bovine serum. When that is not possible, another strategy is to perform virus removal or inactivation processes on media before use, which can prevent viruses from entering and contaminating manufacturing processes. The researchers say that some companies are using a pasteurisation-like process called high temperature short time (HTST) treatment, while others use ultraviolet light or nanofiltration.

“High-throughput sequencing, often referred to as next-generation sequencing (NGS), is one technology that has gotten interest from the industry in recent years and has the potential to address some of the shortcomings of existing approaches. While there is quite a bit of work still needed to ensure NGS is broadly ready for use in the biotech industry, that is one example of a technology with the potential to address this need,” said Barone.

Conclusion

“Our study demonstrated that viral safety is best assured through complementary approaches aimed at reducing overall risk,” said Barone.

Related topics

Biopharmaceuticals, Bioproduction, Drug Manufacturing, Environmental Monitoring, Impurities, QA/QC

Related organisations

Center for Biomedical Innovation (CBI), Consortium on Adventitious Agent Contamination in Biomanufacturing (CAACB), Genzyme, MIT