Study shows the potential to deliver immunotherapy directly to brain tumours

Posted: 30 August 2019 | Rachael Harper (European Pharmaceutical Review) | No comments yet

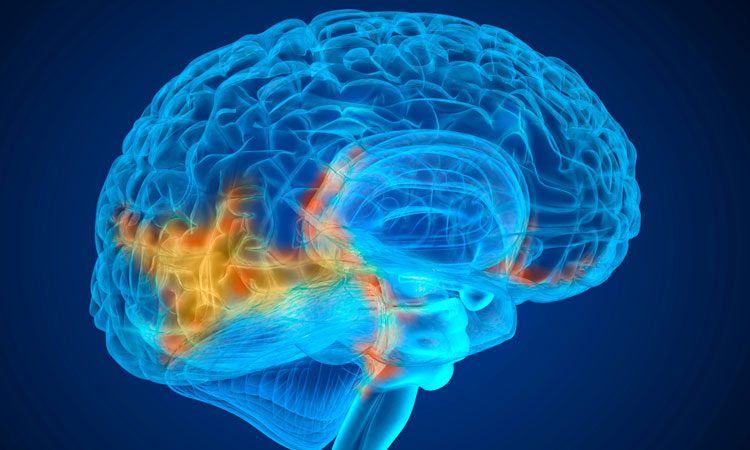

New nano-immunotherapy has traversed the blood-brain barrier in mice, inducing an immune response in brain tissue surrounding tumours.

A new study has given insight into how immunotherapies might one day be delivered directly to the brain in order to treat brain tumours.

The study demonstrated that a new type of nano-immunotherapy traversed the blood-brain barrier in laboratory mice, inducing a local immune response in brain tissue surrounding the tumours – the tumour cells stopped multiplying and survival rates increased.

“This study showed a promising and exciting outcome,” said Julia Ljubimova, MD, PhD, senior author of the study and professor of Neurosurgery and Biomedical Sciences at Cedars-Sinai. “Current clinically proven methods of brain cancer immunotherapy do not ensure that therapeutic drugs cross the blood-brain barrier.

Although our findings were not made in humans, they bring us closer to developing a treatment that might effectively attack brain tumors with systematic drug administration.”

The environment of the brain can be hard to penetrate with drugs or other therapies as the blood-brain barrier can keep out potentially lifesaving treatments. Brain tumours also seem to suppress their local immune systems. Tumours accumulate immunological guards such as T regulatory cells (Tregs) and special macrophages, which block the body’s anti-cancer immune cells, protecting the tumour from attack, Ljubimova said.

In order to allow tumour-killing immune cells to activate, investigators needed to find a way to arrest or deactivate the tumour-protecting Tregs and macrophages.

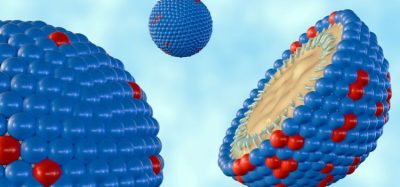

The immunotherapy tested in this study works by delivering checkpoint inhibitors, a type of antibody drug that can arrest and block Tregs and macrophages, so the tumour can’t use them to block the incoming tumour-killing immune cells.

These checkpoint inhibitors are attached with a biodegradable polymer to a protein or peptide that enables the drug to traverse the blood-brain barrier.

With the tumour-shielding cells blocked, immune cells like cytotoxic lymphocytes and microglial cells can then attack and destroy the cancer cells. Ljubimova says that further tests are needed before this therapy can be tested in humans.

The study was published in the peer-reviewed open access journal Nature Communications.

Related topics

Drug Delivery Systems, Immunotherapy, Research & Development (R&D)