Injectable self-assembled nanomaterials developed for sustained drug delivery

Posted: 13 February 2018 | Dr Zara Kassam (European Pharmaceutical Review) | No comments yet

New injectable delivery system can slowly release drug carriers for months…

Because they can be programmed to travel the body and selectively target cancer and other sites of disease, nanometer-scale vehicles called nanocarriers can deliver higher concentrations of drugs to bombard specific areas of the body while minimising systemic side effects. Nanocarriers can also deliver drugs and diagnostic agents that are typically not soluble in water or blood as well as significantly decrease the effective dosage.

“Controlled, sustained delivery is advantageous for treating many chronic disorders, but this is difficult to achieve with nanomaterials without inducing undesirable local inflammation,” said Northwestern University’s Evan Scott. “Instead, nanomaterials are typically administered as multiple separate injections or as a transfusion that can take longer than an hour. It would be great if physicians could give one injection, which continuously released nanomaterials over a controlled period of time.”Although this method might seem ideal for treating diseases, nanocarriers are not without their challenges.

Now Prof Scott, an Assistant Professor of Biomedical Engineering in Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering, has developed a new mechanism that makes that controlled, sustained delivery possible.

Prof Scott’s team designed a nanocarrier formulation that — after quickly forming into a gel inside the body at the site of injection — can continuously release nanoscale drug-loaded vehicles for months. The gel itself re-assembles into the nanocarriers, so after all of the drug has been delivered, no residual material is left to induce inflammation or fibrous tissue formation. This system could, for example, enable single-administration vaccines that do not require boosters as well as a new way to deliver chemotherapy, hormone therapy, or drugs that facilitate wound healing.

Currently, the most common sustained nanocarrier delivery systems hold nanomaterials within polymer matrices. These networks are implanted into the body, where they slowly release the trapped drug carriers over a period of time. The problem lies after the delivery is complete: the networks remain inside the body, often eliciting a foreign-body response. The leftover network can cause discomfort and chronic inflammation in the patient.

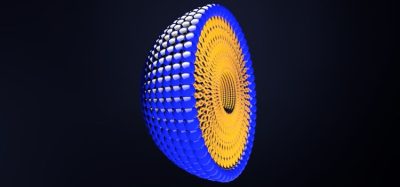

To bypass this issue, Prof Scott developed a nanocarrier using self-assembled, filament-shaped nanomaterials, which are loaded with a drug or imaging agent. When crosslinked together, the filaments form a hydrogel network that is similar to structural tissue in the human body. After the filaments are injected into the body, the resulting hydrogel network functions as a drug depot that slowly degrades by breaking down into spherical nanomaterials called micelles, which are programmed to travel to specific targets. Because the network morphs into the drug-delivery system, nothing is less behind to cause inflammation.

“All of the material holds the drug and then delivers the drug,” Prof Scott explained. “It degrades in a controlled fashion, resulting in nanomaterials that are of equal shape and size. If we load a drug into the filaments, the micelles take the drug and leave with it.”

After testing the system both in vitro and in vivo in an animal model, Prof Scott’s team demonstrated they could administer a subcutaneous injection that slowly delivered nanomaterials to cells in lymph nodes for over a month in a controlled fashion.

Prof Scott said the system can be used for other nanostructures in addition to micelles. For example, the system could include vesicle-shaped nanoparticles, such as liposomes or polyersomes, that have drugs, proteins, or antibodies trapped inside. Different vesicles could carry different drugs and release them at different rates once inside the body.

“Next we are looking for ways to tailor the system to the needs of specific diseases and therapies,” Prof Scott said. “We’re currently working to find ways to deliver chemotherapeutics and vaccines. Chemotherapy usually requires the delivery of multiple toxic drugs at high concentrations, and we could deliver all of these drugs in one injection at much lower dosages. For immunisation, these injectable hydrogels could be administered like standard vaccines, but stimulate specific cells of the immune system for longer, controlled periods of time and potentially avoid the need for boosters.”

The research has been published in the journal Nature Communications.

Related topics

Nano particles, Nano-medicine, Nanoparticles, Vaccine Technology, Vaccines