Fat cells may inactivate chemotherapeutic drug

Posted: 9 November 2017 | European Pharmaceutical Review | No comments yet

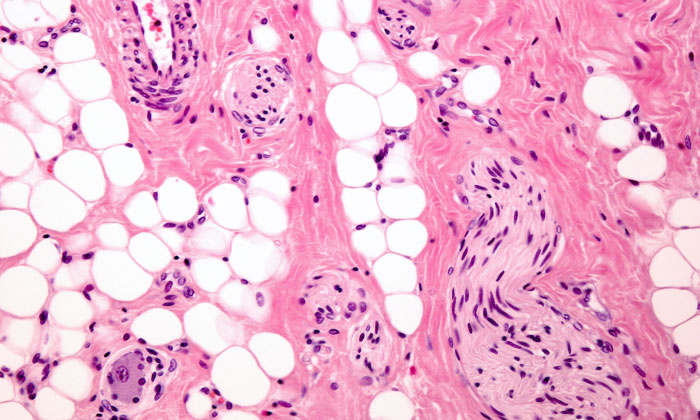

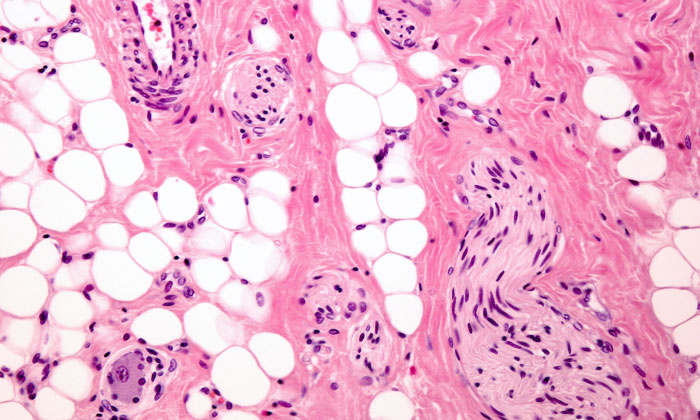

A study has shown that Adipocytes can absorb and metabolise the chemotherapeutic agent daunorubicin, reducing its ability to kill cancer cells.

Previous research has shown that obesity is associated with poorer outcomes from several kinds of cancer, including breast, colon, ovarian, and prostate cancers. Research has suggested that excess adiposity can affect the “pharmacokinetics” of chemotherapy, or the way drugs are absorbed, metabolised, and excreted from the body.

Steven Mittelman, MD, PhD, associate professor of pediatrics and the division chief of pediatric endocrinology at UCLA Mattel Children’s Hospital in Los Angeles, and colleagues sought to examine how obesity might alter the effectiveness of daunorubicin. They cocultured human acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cell lines with adipocytes and treated them with daunorubicin. They also studied whether human adipose tissue from cancer patients could metabolise daunorubicin. They measured the presence of daunorubicin through flow cytometry and liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry, and examined fat cells in bone marrow from children with leukemia.

The study’s key findings, according to Mittelman, are:

- The presence of adipocytes significantly reduced the accumulation of daunorubicin in the ALL cells.

- The adipocytes absorbed the chemotherapeutic agent, removing it from the leukemia microenvironment. The leukemia cells treated with daunorubicin survived and proliferated better in samples that contained adipocytes.

- The adipocytes metabolised daunorubicin. Enzymes in the fat cells changed the structure of the chemotherapy molecule, making it much less toxic to the leukemia cells.

“The finding that human fat cells can metabolise and inactivate a chemotherapy is novel and surprising,” commented Mittelman. “This is important for leukemia and a lot of other cancers that grow in the bone marrow or around fat cells, since that means that fat cells might remove chemotherapy from the environment and allow the cancer cells to survive.”

Fellow author Etan Orgel, MD, MS, attending physician at the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and an assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California, said the study’s findings indicate a need for further research to determine whether adipocytes have a similar effect on other types of chemotherapy, and if a similar effect occurs in other types of cancer.

“A deeper understanding of the process could lead clinicians to deliver more effective treatment by choosing or designing chemotherapy drugs that are more resistant to the enzymes in fat cells,” he said.

Mittelman said the study’s primary limitation is that the researchers were unable to measure the exact concentration of daunorubicin in the leukemia cells in patients.

The study was published in the journal Molecular Cancer Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

Related topics

Anti-Cancer Therapeutics, Chemotherapy, Flow Cytometry, Liquid Chromatography - Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS), Pharmacokinetics