Scrubbing up the environment

Posted: 26 August 2021 | Kayleigh Clark (University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust [UHBW]), Kevin P Griffiths (University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust [UHBW]), Rhiannon McCarroll (University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust [UHBW]), Sean Fradgley (University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust [UHBW]) | No comments yet

Here, colleagues from University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust (UHBW) share the beneficial impact of reduced cleanroom environmental contamination following an upgrade to their facilities and procedures.

Introduction

The Pharmacy Production unit at University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust (UHBW) is a UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Agency (MHRA)-licenced facility that holds a Manufacturers Specials (MS) licence and Manufacture/Importation Authorisation for Investigational Medicinal Products (MIA(IMP)). The unit carries out aseptic preparation of injectable doses and eye drops as well as non‑sterile production of oral and topical dose forms.

At an MHRA inspection in April 2017 it was reported that the changing facilities required improvement, as employees had to pass through an unclassified area straight into a grade C area with only one change. As a result, outdoor clothing, along with environmental contaminants, were being brought into changing areas that led to grade B and C cleanrooms. This was in direct contradiction to the current recommendations within the EU Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) Annex 1. To address the deficiency, a business case and a bid for capital funding was submitted to finance a refurbishment of the department to build improved changing facilities. The improved changing facilities would enable staff to wear dedicated clothing within the department instead of their own ‘outside’ clothes. The refurbishment would also provide improved hand washing facilities at the point of entry to the department and a new assembly area for aseptic products to improve the process flow for aseptic work. The business case and bid for capital funding, supported by evidence of deficiencies reported in the inspection, was successful and a budget was allocated for the refurbishment work.

In addition, the Quality Assurance team (responsible for assessing environmental monitoring plates and creating action reports for any out of specification [OOS] results) had reported concerns regarding the number of action reports being issued for certain locations. Areas of key concern were cleanroom 4 and its associated change and the initial change room 1 used for entry to the aseptic suite.

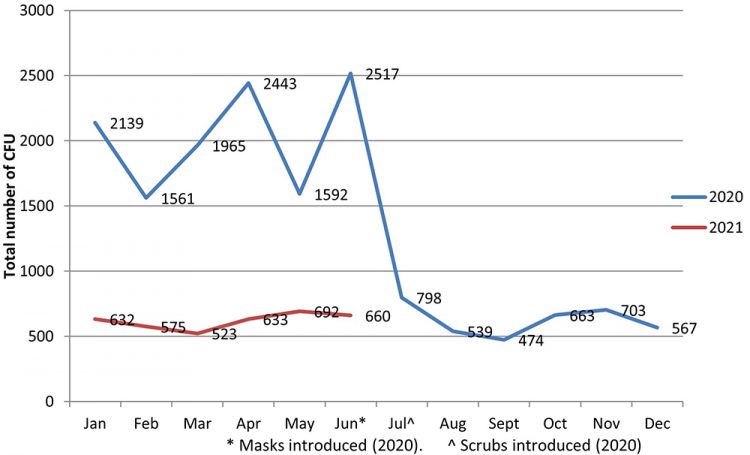

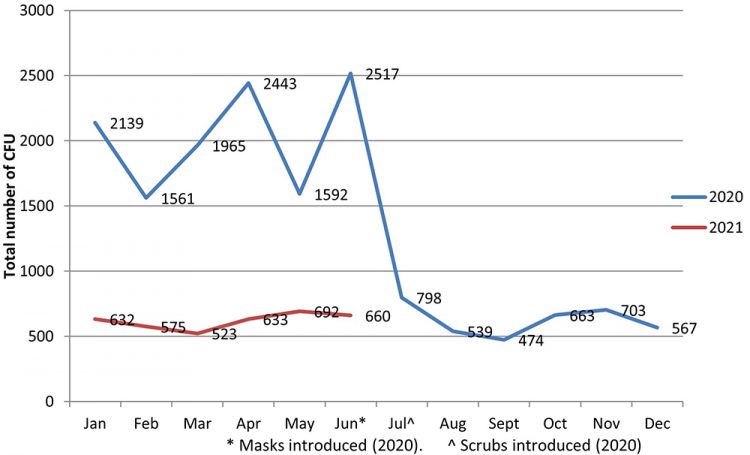

Following the introduction of wearing scrubs, we noticed an immediate and significant reduction in the number of colony-forming units (CFUs) being grown on the department passive settle plates”

In early 2020 the refurbishment of the department was completed and focus was turned towards dedicated clothing for staff to wear within the department. It was decided that the staff would change into scrubs on arrival, that these would be worn for the duration of the day and then sent for laundering at the end of each working day. Feedback received from staff regarding practicalities and working processes led to a suggestion of having two sets of scrubs. Light pink scrubs would be worn by the staff under their cleanroom garments when working in the grade B cleanrooms, while burgundy ones would be worn in the rest of the department. This decision was adopted on the provision that supplies of scrubs be readily available within the hospital, that there was a supply of scrubs that could be separated from the scrubs in general use around the hospital and processed separately, and that the scrubs could be laundered on a daily basis using the trust linen contract and following procedures that were already in place for the hospital. It was possible to introduce the scrubs at a relatively low cost, particularly when compared to the cost that would have been incurred had we obtained clothing from our cleanroom garment supplier. The wearing of scrubs was introduced on 1 July 2020 following a change control process and this was well received by the staff.

Changes in environmental monitoring results

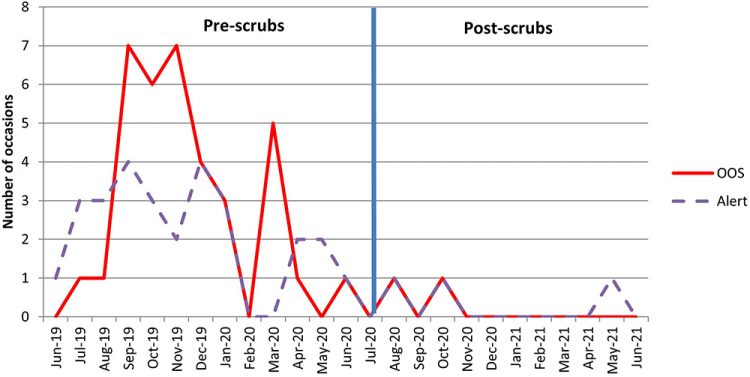

As expected, following the introduction of wearing scrubs, we noticed an immediate and significant reduction in the number of colony-forming units (CFUs) being grown on the department passive settle plates. Figure 1 illustrates the number of CFUs detected on passive plates within the aseptic unit dramatically decreasing by 68 percent in the first month. Furthermore, this reduction in CFU numbers has been sustained and we now have a whole year of data showing this decrease. After the intervention, the mean number of CFUs detected reduced from 2,036 (Jan-Jun) to 624 (July-Jan).

Figure 1: Number of CFUs identified on passive settle plates within the aseptic suite before and after the introduction of scrubs (July 2020).

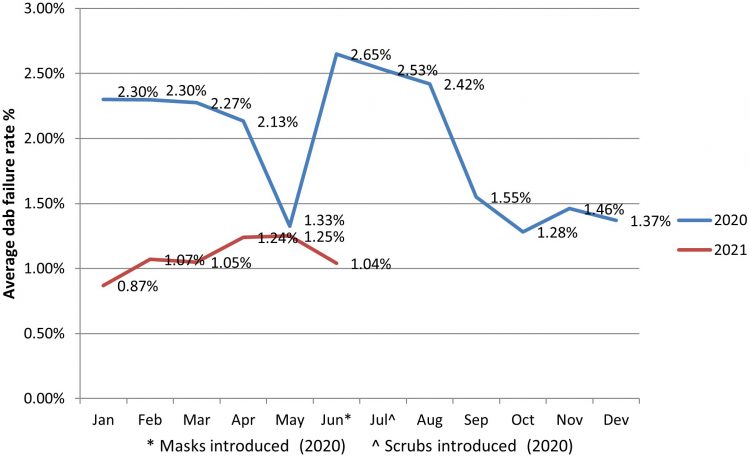

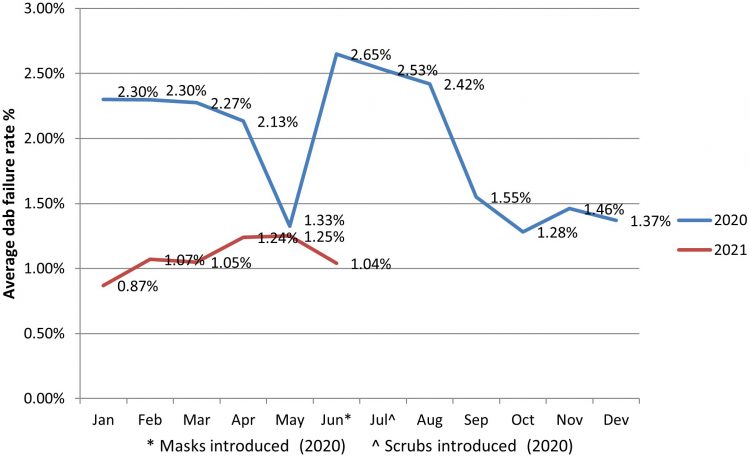

Another positive and immediate result, along with observing a reduced number of CFUs on passive settle plates, was a decrease in operator finger dab failure rates (as shown by Figure 2). The finger dab failure rate reduction (along with other measured quality assurance controls) provides continued confidence in the preparation and supply of safe injectable medicines.

Figure 2: Finger Dab failure rates for the ‘main’ aseptic operator (based on rolling 40 sessions) before and after the introduction of scrubs (July 2020).

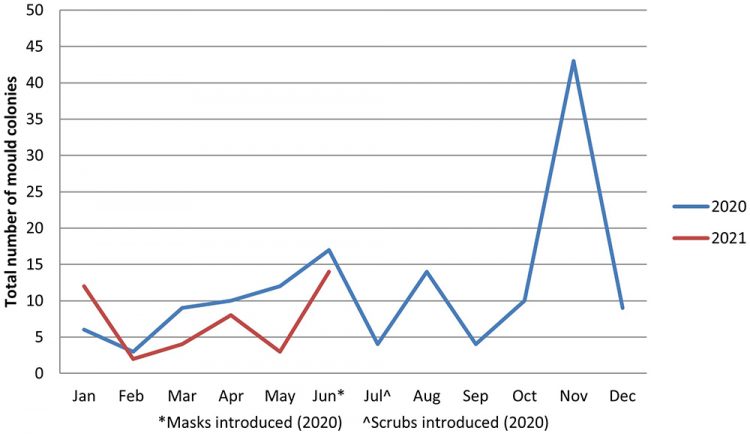

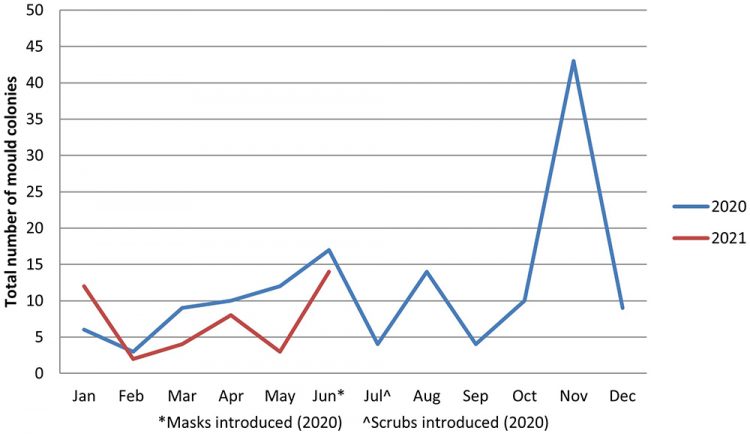

Unusually, the numbers of recorded moulds detected across passive and active air sampling plates have remained relatively stable (Figure 3), suggesting that the new gowning procedure has had less of an impact on reducing mould and fungi contamination within the production unit. A high‑level investigation into the anomaly results seen in November 2020 established a deficiency associated with tray cleaning – specifically, those used to transfer stock to and from the department – and was noted as the probable root cause.

Figure 3: Mould growth detected on passive and active air sampling within the aseptic unit before and after the introduction of scrubs (July 2020).

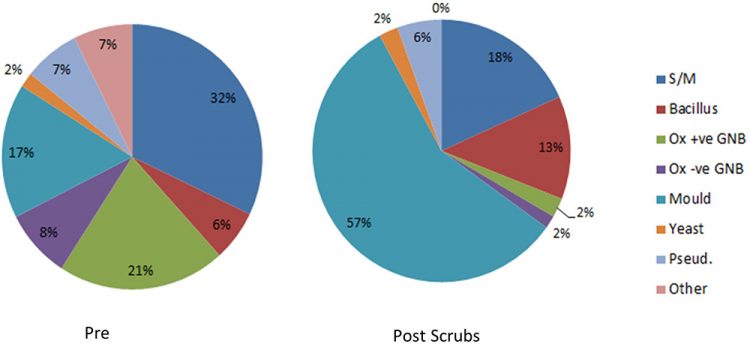

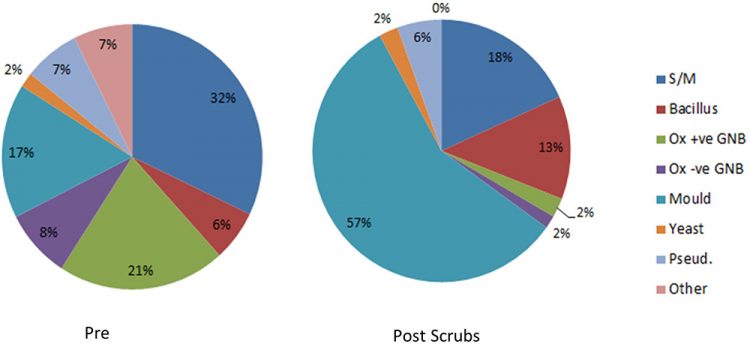

From July 2019 to July 2020, 261 colonies were identified as Staphylococcus/Micrococcus sp. This dropped to 56 colonies for the same time period between 2020 and 2021. The predominant organisms previously grown in the department have been skin commensals (Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus haemolyticus, Micrococcus luteus and Kocuria rhizophilia) and this is an area where a reduction in CFUs has been greatest (Figure 4).

Figure 4: CFUs identified on passive plates between January and June 2020 (pre scrubs) and July to December 2021 (post scrubs).

Additionally, in June 2020 wearing surgical face masks became compulsory in healthcare settings as part of the UK response to the COVID-19 pandemic – a factor that was considered when assessing the impact on the number of CFUs being grown on settle plates. However, given there was no immediate reduction in CFUs in June (ie, when face masks were worn), this change was considered less significant than the immediate reduction witnessed in July 2020 following the introduction of scrubs.

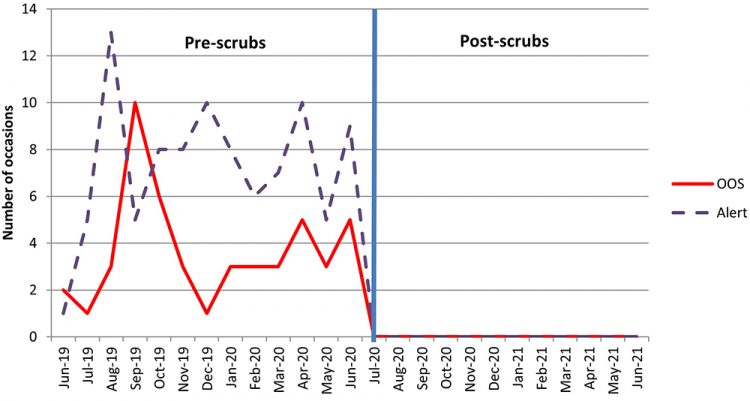

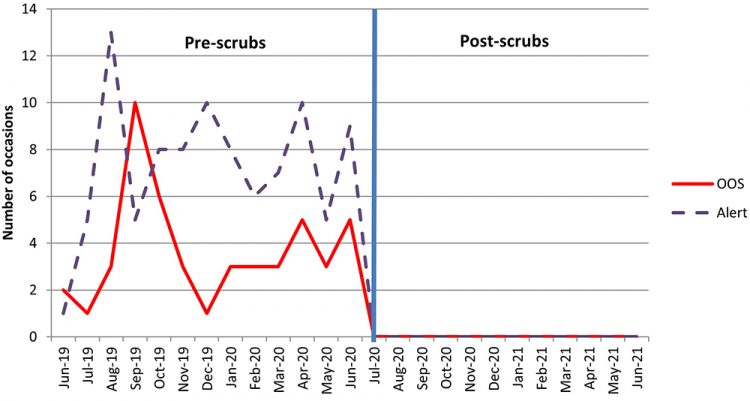

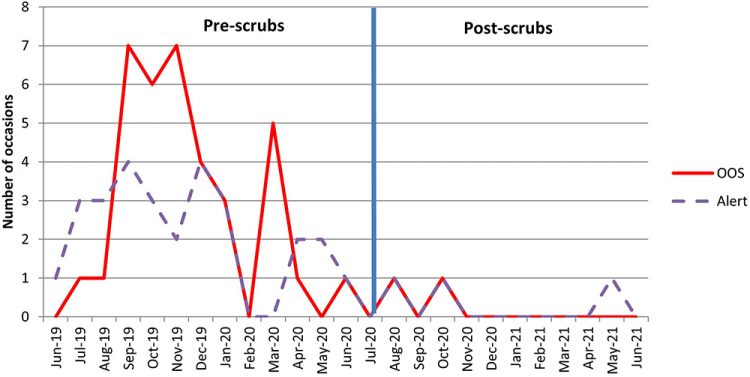

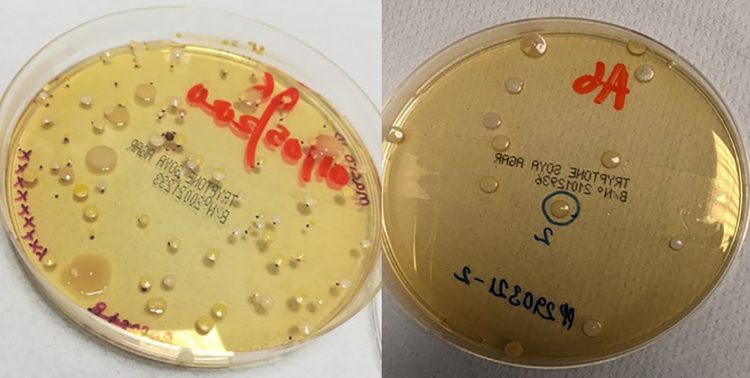

The most significant reduction in passive plate CFUs has been seen in the cleanroom changing rooms (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5: Total number of OOS and alert levels triggered on Change 1 plates between 2019 and 2020.

Figure 6: Total number of OOS and alert levels triggered on Change 4 plates between 2019 and 2020.

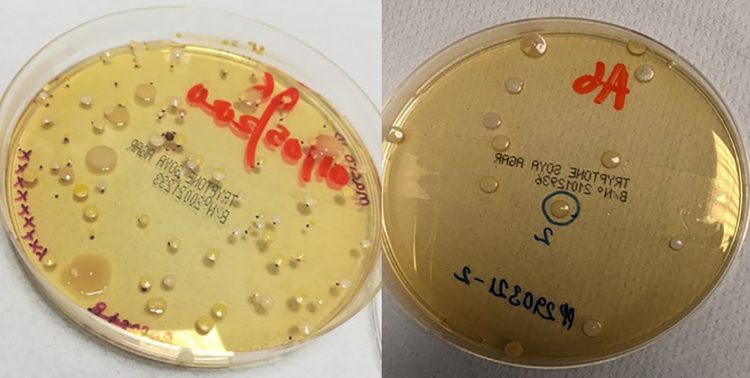

Prior to the introduction of scrubs, staff were required to remove their outside clothing in the changing room adjacent to the cleanrooms and strip down to their underwear before donning their sterile cleanroom suits. The new change procedure, which requires the addition of a cleanroom suit over the cleanroom-specific scrubs (rather than removal of clothes) is likely to have reduced the shedding of particles and skin cells associated with the removal of outside clothing in the changing rooms, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Example of Change 1 passive plates before (left) and after (right) the introduction of cleanroom scrubs.

Conclusion

The combination of the newly reconfigured change facility and the introduction of scrubs were demonstrated to have had a profound beneficial impact on environmental contamination detected within the hospital aseptic cleanroom facility. Observations of trended growth media sampling results from the routine environmental monitoring programme showed a significant reduction in the quantity of micro‑organisms detected following the introduction of scrubs. Importantly, this is indicative of a general decrease in the overall bioburden in the cleanrooms and a reduction in the risks of contamination of the aseptic products with bacteria, which could pose a clinical risk to the patients receiving them.

The improvement has addressed the major GMP non-compliance regarding changing. Additional benefits have been associated with capacity and cost savings. Reductions in OOS plates have resulted in less time being spent compiling and completing OOS reports. These savings have been made as fewer plates have required further identification services.

About the authors

Sean Fradgley PhD BSc (Hons) MRPharmS is Associate Director of Pharmacy, Quality Assurance at University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust (UHBW). Following professional registration as a practising pharmacist in 1988, Sean has gained experience within the academic research environment, which included completion of a PhD in breast cancer (1993). However, since 1997 Sean has focused on hospital pharmacy, specifically within the specialist field of quality assurance through employment at a variety of trusts. His responsibilities within the current post include management of a specialist team to ensure continued regulatory/GMP compliance and support across Technical Services for the provision of pharmaceutical aseptic services and non-sterile manufacturing, maintenance and development of the quality management system, QC MGPS support for medical gases and a variety of validation and project work.

Kayleigh Clark is Deputy Quality Controller and Clinical Scientist at University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust (UHBW). She has over 10 years GMP experience working within Pharmacy Technical Services (including Radiopharmacy) and has recently completed the NHS Scientist Training Programme.

Kevin P Griffiths BPharm MRPharmS is Pharmacy Production Manager at University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust (UHBW). Kevin has been qualified as a pharmacist for 29 years and spent most of that time working in NHS Pharmacy Technical Services, the last 23 of which were in large, licenced hospital production units. He has particular interest in classical sterile and non‑sterile manufacturing as well as aseptic preparation.

Rhiannon McCarroll is Quality Assurance Technical Officer at University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust (UHBW). She has six years’ experience of statistical research within psychological sciences, two years GMP experience and is new to the exciting world of pharmaceutical QA/QC.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the UHBW Pharmacy Production and Quality Assurance teams and particular thanks to Charlie Ross, the Pharmacy Production Capital Projects Manager, for his work on the Pharmacy Production refurbishment and the implementation of scrubs.

Reference

- MHRA. Annex 1: Manufacture of Sterile Medicinal Products, In: MHRA (eds.) Rules and Guidance for Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Distributors. 10th ed. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2017. p98.

Issue

Related topics

Analytical techniques, Aseptic Processing, cGMP, Cleanrooms, Drug Safety, Environmental Monitoring, Microbial Detection, Microbiology, QA/QC, Regulation & Legislation